-

Pages

Tags

Latest posts on Transition Town Kenmore Blog

Latest posts on Transition Town Kenmore Blog- FIND US ON FACEBOOK. THIS BLOG IS INACTIVE October 12, 2017

- TTKD Nov 2013 meeting: Sustainable Local Food November 14, 2013

- Who'd have guessed? Increasing renewables really does decrease carbon emissions October 15, 2013

- TTKD October meeting: The Story of Stuff October 8, 2013

- Australian heat records keep tumbling October 8, 2013

Archives

Proudly supported by

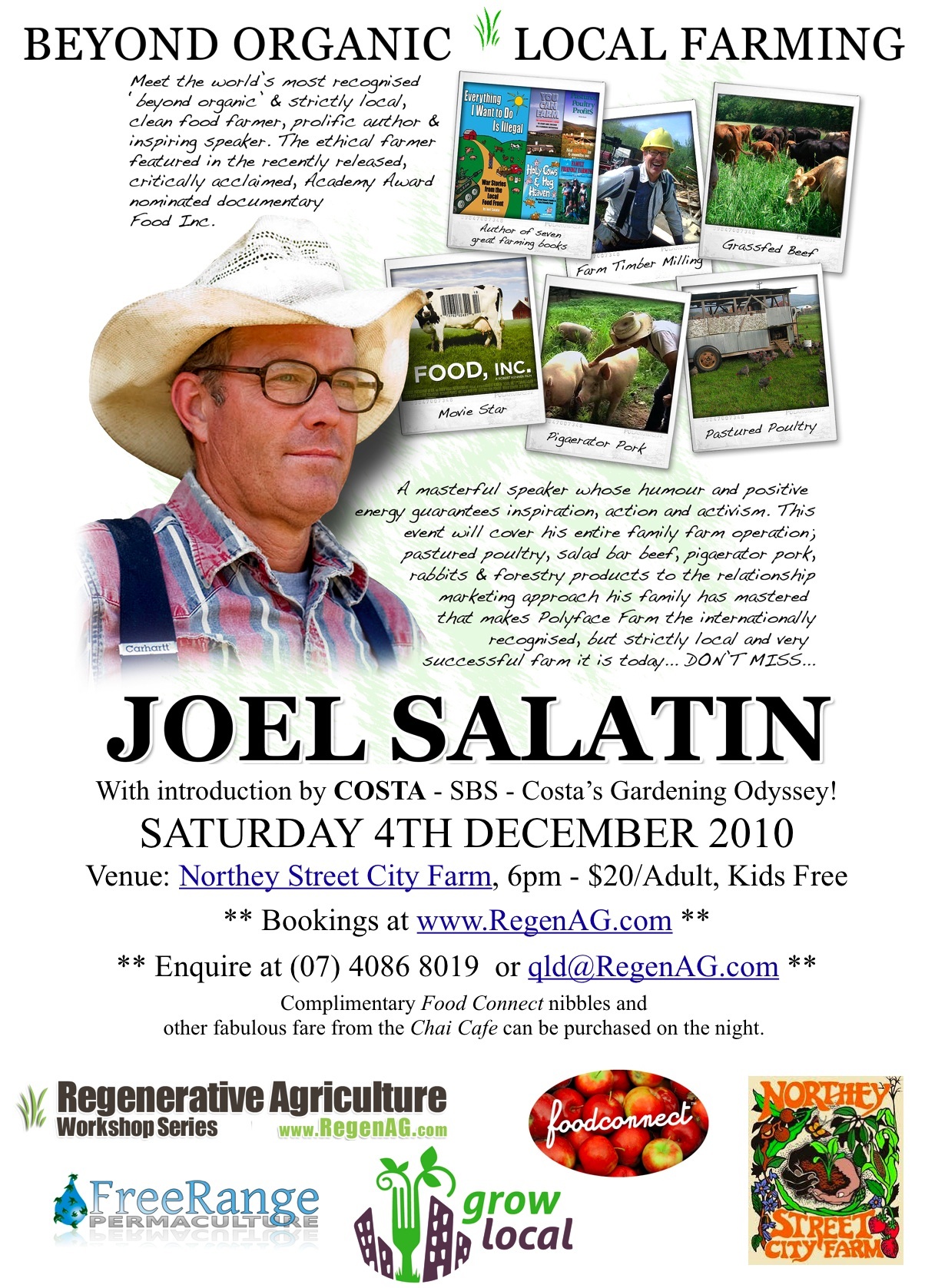

The Lunatic Farmer has a message for us City Folk!

This entry was posted in Uncategorized. Bookmark the permalink.

I’d not before seen this large, luscious dell in this unlikely location, replete as it was with vivid colours, fresh and subtle scents, and nutritional propensity in natural sweet and savoury packages. The pre-event vibe seemed something between a protest rally, a feel-good hoe-down, and a formal public lecture. The crowd that had gathered wore largely mainstream, but down-played garb, though a few had the look and distinct ‘hippy’ feel one might expect at a place and time such as this.

It was like the coalface, the outpost for the real war against terror, made all the more real for the fact that the several folk I’d asked for directions in approaching this refreshing pocket of permaculture either knew it not, pretended to know (thus throwing me off the scent), or ignored me altogether. Being here would almost seem like a clandestine operation were it not for the fact that council assistance had been given in preparation for the event.

At first, and prior to the commencement of the speakers (while the large, red-topped arena slowly darkened with the setting of the sun, and the stage lights illuminated largely written slogans and facts on old bits of timber, reminding us of how destructive corporate food can be) I think it was the people in attendance that interested me most. While some bandied around organiser’s names and chatted casually with ‘the help’ (provided generously by Food Connect volunteers, and the Northey St. farmers themselves), there were still several who seemed to carry about them the usual city air of resigned confusion, varyingly layered with wide-eyed curiosity. The mainstay of these slightly uncertain folk constituted the partners of those with a general (and undoubtedly genuine) interest. But we all seemed to agree on (and most, I suspect, enjoyed) the fact that what we were doing was pissing off someone some-where high up in the ranks of Monsanto.

A bright and friendly introduction by a spritely young lady with a well-measured level of enthusiasm set an appropriate tone for the evening. It may have been the first Emperor of China, Qin Shihuang, who unified many warring factions in the 3rd century B.C.E. and brought about a Dynastic system of leadership that persisted for over 2000 years, that suggested that one should consider important things lightly (and not-important things heavily), and while we were certainly dealing with what most (if not all) in attendance would consider some highly important issues, the talks progressed with a relaxed heartbeat pulsing so as to provide many laughs and cheers throughout.

Following the introductory speaker came Mr. Kym Kruse from RegenAG (http://www.regenag.com/) who, with many genuinely warm smiles and kind steady eyes, told us of the successes that he and their diligent crew have been able to find in North Queensland through following a regenerative agriculture modus-operandi. He spoke of 4 workshops less than a year ago that began their toil in the region, which had comprised of some well known and intelligent people encouraging folk toward adopting more sustainable and sensible farming methods. Following a short presentation ceremony in which several gifts were given to key people, Mr. Kruse handed the microphone to Costa Georgiadis (of Costa’s Gardening Odyssey fame) who elevated the crowd with an entertaining, no-bullshit 8 minute talk.

From the outset, Costa began to spot a few elephants loitering in the dialogical chamber that had been created, and set about making some key elements explicitly understood. The crowd seemed to wake a little with each ‘pop’ that the elephants made as they flitted from this dimension to the next (or perhaps out of existence altogether). First on his list was the ‘specialness’ of the occasion, and what an opportunity this was for us all to (not only) learn for ourselves some great tips for bettering our food intake (and, perhaps, our karmic footprint), but to also contribute to a movement that has begun to shake the foundations of an unclean and selfish system, with a view to replacing the muck with beauty and decency. Second, he told us something that we all knew, but would most likely not have thought to acknowledge, either to ourselves or with whomever may have been nearby. Each of us there, each and every single one of us (either sat on a seat or stood casting an occasional eye skyward for fear of rain) had something that made us very much the same as all of the others in attendance; we all ate – and we all pooed. This, he stated, is enough for us all to fairly be considered farmers, whether we’ve experienced the joy in planting a crop and seeing it to maturity or not.

After cleverly and humorously putting us in the mood to hear some home truths, Costa began to discuss where the impediments to healthy food production lie. Included were the political truths surrounding mining in this country, and how a great deal of perfectly useable land is being literally turned inside out so that certain arid people can further their already incredible wealth, and machines that ferry foodstuffs tens-of-thousands of kilometres can be manufactured and fuelled. We were reminded that Australian legislation seeks to support this pursuit, rather than consider using that very same land to harvest crops or rear livestock for local consumption, and the possibility that many (perhaps the majority of) politicians in this country would rather support the former endeavour than encourage local food production was given due (and, I felt, fair) respect.

All this was a crescendo toward what (for me, at the very least) was the main buzz word of the evening: “Convenience”. Costa quickly put into perspective the fact that supermarkets and convenience stores take advantage of those of us who are unwilling to try growing their own food, unable to attempt doing so because of time commitments, or are unknowledgeable about the process; but that by controlling our food consumption in this way, an average evening meal may have (collectively) travelled 3 times the circumference of the Earth. This startling revelation is the main impetus behind the work of people such as Joel Salatin (and Mr. Georgiadis), and organisations like Food Connect, Transition Towns, and Permablitz.

In building upon this point, Costa quoted a Zen Buddhist monk that he’d met in Switzerland, who had said “When waiting, just wait. When eating, just eat. When being a chicken, express your chickenness!” The agri-business model, the followers of which seem entirely unaware of this philosophy, has no intention of allowing chickens to be chickens, and this (in itself) compromises the potential quality of the food they produce. “Food is not about convenience” he stated, “convenience food is killing us.” To back up this statement, Costa pointed to the example of the trans-fats that are found in your average hamburger that go a long way toward clogging arteries and causing all manner of health problems for both children and adults alike.

So, the inevitable question of the evening presented itself; how are we to combat this compassionless and greedy method of pseudo-sustenance? In tackling this quandary, Costa called upon the consistently wise words of the late Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who once said that “first they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, and then you win.” The issue (in this instance, and at least in the collective opinion of the presenters), lies largely focussed in wrestling with the distribution of food. The bottom line, according to Costa, is that if we can remove the need for a distribution industry, then the agri-business model will (somewhat both ironically and literally) have no legs to stand on. And the best way to do that, he continued, is to start the production of our own foods; either in our own back-yards, or in some communal land somewhere (either offered by the good grace of some-fortunate someone with it to spare, or somehow procured via a collective bargaining process), which ultimately does not require billions of tonnes of transportation fuels each year to feed people. Suffice to say, this was certainly the most appropriate moment to introduce the main presenter for the evening, the ‘lunatic farmer’ himself, Mr. Joel Salatin.

Finely presented in smart-casual attire, and speaking with a smooth (almost southern) American drawl, Mr. Salatin immediately upped the tempo beneath the large red canvas by offering a generous and all-embracing presence that would have equally suited either a Blues-Brothers Tribute-Band or a Gospel-Spiritual Choir as backing. After the fine and well woven flurry of introductory statements, Mr. Salatin seemed quick to find comfort and ease with our foreign atmosphere. He wasted little time at all in considerately commanding his audience to welcome the 6 basic principles that he was to cover in varying degrees of depth in the presentation that followed; production; processing; accounting; marketing; distribution; and patronage. With little by way of ado, Joel blended his suave and serious nature well to move us quickly into considering the first of these, deftly mentioning time-constraints upon the evening as being worthy of prime consideration.

Production

Mr. Salatin quickly led us to consider that producers build soil, rather than erode it, stating (with well practiced gestures for accompaniment) that there are “more living things in 1 handful of healthy soil than [there are] humans on all the earth”. This was contrasted bluntly with the general populous view (as held by the majority of those in ‘western’ societies) that Brittney Spears is far more interesting and/or entertaining than the incredible wonders to behold through undertaking an investigation of nature. The implicit/explicit line here was very thin, and I suspect that many in the crowd knew exactly what he was trying to say; the popular commercialist media were doing a fine job of keeping us all blissfully ignorant of the truly astounding processes at work both around and within us.

However, the conspiratorial air was kept thin at this stage while (instead) the thrust of his speech vibrated the thick atmosphere between us so that we could all appreciate the notion raised that it is in considering and caring for the soil that feeds and nourishes all land-dwelling plants and animals on this planet (save perhaps for those few species that inhabit volcanoes and constant sub-zero-Celsius conditions) that the most benefit can be gleaned from and by the producers of food, upon whom our very lives rely. In expanding on this requirement, Mr. Salatin described that both farms and food must be “sensually magnetic”, that they must entice and inspire us to enjoy what we consume.

To illustrate the contrast (and the current actuality of our food sources), Mr. Salatin conjured multi-sensual imagery of farms that are often smelly and poorly crafted, largely due to money-focussed organisations ignoring the propensity of inter-speciation farming to encourage about better production (such as encouraging pigs to run on a tread with a healthy bucket of corn as inspiration so that a simple machine to service other elements of the production process may operate); instead opting for a mono-species practice based on a decision to cater for a certain market. At this delineation between these practices, Mr. Salatin considered that “food is fundamentally biological, not mechanical”, intentionally made explicit so as to indicate that mechanically produced food for convenience purposes direly lacks that magnetic aspect. Farming of the machinated kind, in Mr. Salatin’s view, is inevitably (and detrimentally) wanting of a sacred connection, a connection that can only be fostered through recognising and appreciating the intricate and gross, and the overt and subtle interconnections that exist between all living things, which he advocates is necessary for the farmer if s/he is to produce goods that leave the consumer glad to have chosen that particular delectation (and possibly pondering what else might be done in the culinary realm so as to enhance life’s pleasure).

The contrast made between the mechanised farms and biological farming processes reached its pinnacle of elucidation with Mr. Salatin stressing that biological farming requires that we, the farmers (the eternally eating and pooing types that we are) should respect and/or cultivate growing and nurturing practices that seek to intertwine living beings into a well crafted synergy, and, in so doing, encourage better health through better produce.

Almost as an aside (but a certainly necessary contribution, not least of which for how it applies for those with children), the speaker then talked of encouraging young-ones to begin gardening and farming while at a tender age. In particular, Joel weighed up the structure of computer-games with that of ‘real-life’ situations by suggesting that in a computer game, a ten second interval is all that is required before another attempt is made at reaching the goal of the task. Should a life be lost or car be crashed, everything is returned to as it was when the task started, completely annihilating the necessity to mourn the loss. By contrast, if one is to attempt to grow a garden and (due to poor methods) a series of plants die, the effect is irreversible. By offering the crowd this perspective, I believe Mr. Salatin (quite subtly, but successfully) guided us into the anti-chamber of considering the beneficial psychological impacts that growing food can cultivate. (The issue of the psychological impacts re-emerged later, which only served to sweetly enhance the recognition of just how interlinked all the information presented really is…) However, another obvious benefit for the encouragement of children into gardening and farming practices was made clear – if bright and intelligent individuals can be drawn to such practices, then the movement to cease the current agri-business hold on all that is edible can only be better served. And on yet another, equally deep level, this not only provides hope for the generations to come, but also places the control in our hands for how the future can be shaped.

Processing

Joel began this part of the lecture by reminding us of what Costa had briefly covered in terms of governmental regulation, and who it is ultimately set to serve. He introduced his perspective on this issue by asking us to consider “who owns me?” He described how our bodies are home to 3 trillion creatures of varying kinds, and blatantly suggested that (as custodians over their home) we have the responsibility to ensure their survival as best we can. This fascinating perspective strikes an harmonious chord with my own views on the sacred nature of life of all kinds, and that he successfully avoided the obvious point that we should aim to be healthy ourselves also (a much belaboured argument for better food practices) was, in my assessment, to his credit.

Mr. Salatin argued that we need more and better targeted regulation of foodstuffs, in all aspects of the agriculture cycle. He talked of how it only makes sense that by passing laws (for instance) on the maximum levels of pathogens permitted in food will healthier eating by the consumer be the necessary consequence. Instead, the US government is seeking to remove the right of people to grow their own produce by introducing laws unashamedly designed for the benefit of the agri-business corporations. The point was then raised that Australia has a history of following what the USA decides to do, and that we must recognise the rising tide for what it is, and take steps now to guard our land against this slowly moving, but devastating tsunami of politically backed corporate greed. The difficulty though is the direly painful amount of bureaucracy involved in instigating governmental action (without, that is, having an almost inexhaustible amount of money behind you to hurry things up).

Accounting

Joel’s view on this is simple. Someone has to look after the money. (My view, as many have endured many times before, is that we should do away with the stuff altogether. Money is surely too simple a device of interaction for reasonable, intelligent and truly discerning people.)

Marketing

Salatin makes it plain – “most of us are farmers ‘cause we don’t like people!” (Hence, marketing practices are found to be something that farmers tend to shy away from.) More than this though is the fact that often farmers find it difficult to face the prospect of rejection that selling their produce can bring. Years of hard work and love-filled emotional labour have brought to fruition their goods, and so it is not hard to empathise with how stressful it can be to risk seeing a bumper crop go to waste.

Therefore, it is necessary to find those with the ability to interact in that special way that only marketeers can. Joel drew on the example of many farmers in the ‘States who call upon cousin’s in the city to do the real dirty work, but suggested there are many ways to address this issue. Hiring staff specifically for the role (should the farm be profitable enough) is just as common a practice.

Distribution

As mentioned before, this is the pyre the local produce movement wishes to light so as to (ultimately) see the Phoenix rise. Without the need for a complex and costly distributive system, a great deal of capitalistic endeavours would be seen to crumble, and so it is imperative that as many people be encouraged to be a part of local food production as possible (and for a dual reason). If enough can be a part of this push to cause a quake in the money-sucking pockets of this world, then one would want to hope that there are enough ready to teach and train the refugees left over after the economy follows Atlantis. Mr. Salatin pointed to the fact that this is the reason why the Monsanto Corporation are extremely concerned about the movement of which he, I, and many of you who read this have chosen to be a part. (It is at this point that an elephant of an unknown number is finally forced from the room with a rather satisfying ‘pop’ indeed!)

Patronage

Mr. Salatin opened this final section of his speech by pointing out the slightly odd, and (as a fan of culinary preparation myself, in my opinion) rather distressing fact that kitchens are disappearing from the design of apartments. An example elucidating this bizarre and worrying prospect is given with the recant of a conversation that Joel (I believe it was) had with a primary school teacher. S/he had asked the children to bring to class an old cooking pot from home that they were going to paint as an activity. There was one child (however) who didn’t have access cooking pot at home! It came to light that there was simply no kitchen in the child’s place of residence, and that any meal cooked in the house was done so using microwave technology (and so no pots, of any kind, were available).

How is it that we have reached such a point where cooking is less common, and even that not cooking at all (at any time) is becoming accepted? Besides the usual suspects commonly lined up in our convenience culture; that ready-prepared meals are readily available, and that the bulk of people are experiencing increasingly wearying and time-occupied lifestyles, a further explanation offered is that this trend began some time ago, during the baby-boom period. As a result, there is now a generation of people who have not had the opportunity to learn the art of cookery through those that reared them (if practiced through the appropriate emotional lenses, as, some might contend, it bally-well should be, cooking is indeed an art).

Salatin stated that he views cooking as a sacred act. What one is dealing with when one cooks is the most delicate (and hence sacred) of issues; that a life that has been intentionally ended so that another may continue.

Inextricably entwined with the cooking endeavours (when working in a locally produced food context) is the notion of appreciating seasonality – something which has been forced into a dark corner by the agri-business model. No longer do we feel the anticipation of the coming season for the next wave of foodstuffs it brings; those fleeting pleasures we enjoyed last year and have missed in the time since our last encounter. In this way, we are living in a world where we are appreciating less and less the food we have on offer (almost paradoxically) as a direct result of it being on offer at all times. Mr. Salatin stated explicitly that this is not a ‘normal’ way for us to live; our ancestors passed on genetic codes that have primed us to respond more favourably to a seasonal progression of foodstuffs throughout the year, than as we do now with largely taken-for-granted attitudes seemingly rife. There is joy in sacrifice – either self imposed or otherwise. It helps us to appreciate what it was we admired in the things we lost. Without it there is no reason for the anticipation of pleasure to arise upon recognising that what we lost, we did not lose forever.

As a penultimate note, Joel stated that we need not necessarily compromise all our wonderful kitchen gadgetry that this technologically focussed culture we live in has been able to provide. It seems vital to realise that we are in a position to make use of the best that this culture has developed, while at the same time incorporating the best practices that age-old local farming traditions have to offer. It is up to us, each of us individually, to choose what we do with the full gamut of options that are available, but Salatin advocates that we should (or even must) take due consideration where and when we can over what makes for a healthier lifestyle, and a better balanced world.

As a final note, Joel Salatin, the lunatic farmer, drew us back to consider the task ahead. We must recognise that it is political, but that it is also about our right to decide for ourselves what it is we want to see in the future. Although the voting process occurs extremely sporadically, we need not wait for an election to make our stand. By acting now to grow our gardens, to raise our chickens and goats, and to learn and contrive recipes that we share with our neighbours, family and friends, we can make the bastards listen.